RECYCLING

Existing recycling capacity in the U.K. is founded upon the reclamation of resources which are still in a sufficiently prime state to be equivalent to the raw materials they replace, where the cost of reclamation is less than expenditure on extraction of those raw materials. This pattern is illustrated in such sectors as minerals, metals and plastics. Large- scale, centralised and industrialised recovery is inappropriate and less economically viable for many materials, such as bulky organic matter [or putrescible wastes] and many other occasional recyclables, which could have value in organic growing systems and be effectively dealt with by a proliferation of dispersed networks of users.

Recycling capacity could be greatly expanded by measures to harness these underexploited resources. Any measures should be predicated upon the identification of end-users for suitable recyclables. If a sufficiently broad network of local growers could be encouraged to receive and process such materials, mutual benefits could be achieved both in terms of the avoidance of inefficient current practices, such as landfill and incineration, and in the generation of desired end-products; increased organic food output and related benefits. Suitable measures could help achieve targets for the proportion of the wastestream which is recovered and recycled whilst also tangibly benefiting the areas in which they take place.

Crucial to the development of capacity in this field is the fair and efficient administration of existing statutory incentives, such as the requirement on local authorities to recycle 25% of waste by the year 2000 and the availability of credits to organisations recycling waste material.

Many initiatives are already in place to demonstrate the efficacy of such measures, the best example being in the case of the composting of municipal refuse. However, current capacity is geared to limited objectives, ignoring closely related materials such as the processing of autumn leaves into leafmould, a superior substitute for peat.

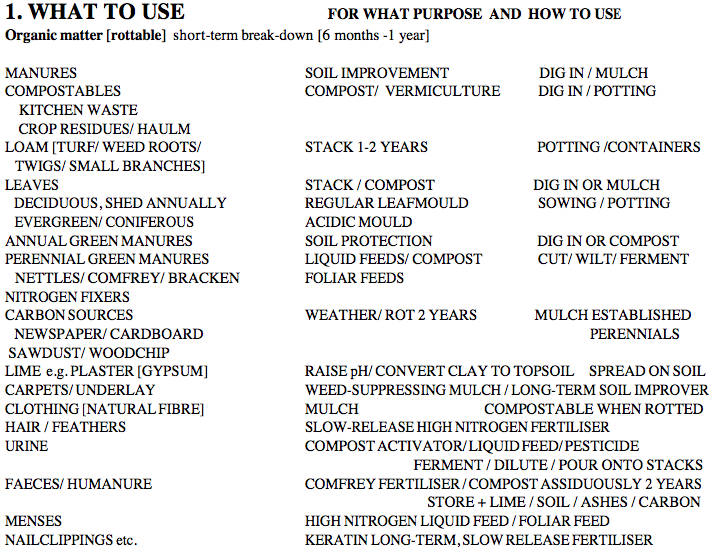

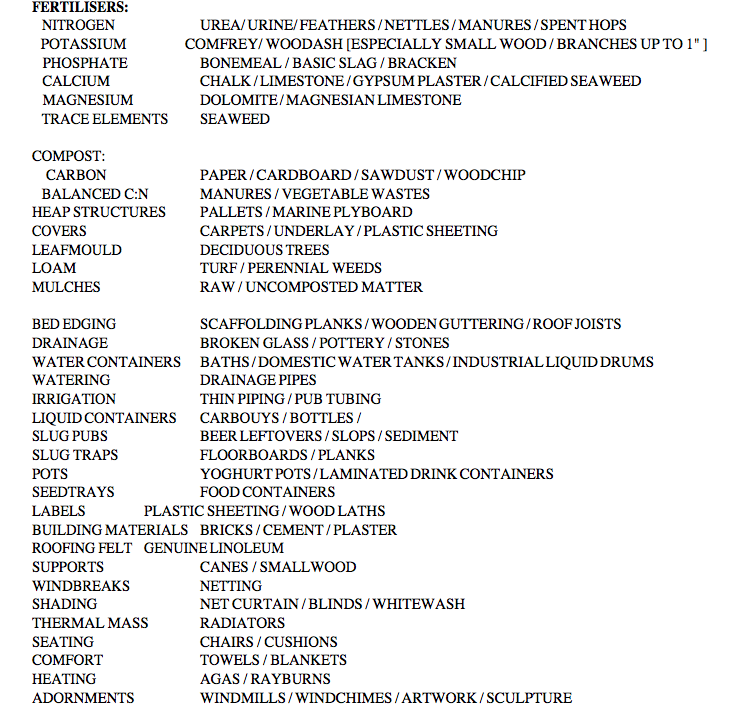

Effective commitments to achieve these objectives could include the interception of materials suitable for organic food growing before they are taken to landfill or incineration. Guaranteed prices for quantities of these resources could support increased employment opportunities in the reclamation industry to supply the needs of organic food growers. Lists of such resources are included in article below.

In the case of many materials, it would be justifiable to accumulate, stockpile and store them indefinitely, awaiting use. Similarly, drop-off sites close to production, such as on derelict allotments accessible by road, could be managed to allow waste processors to divert materials away from other destinations.

This pattern could be expanded to include regional databases and directories, performing the role of clearing houses for matching supply and demand of available resources. The improved environmental impacts of operating such schemes would justify public investment to subsidise them at least initially, stimulating cultivation in the areas where this happens. Private industry is already being motivated to develop in this direction by pressures such as increases in the landfill tax.

Extract from SOFI – its formation – 1998

RECYCLING FOR ORGANIC FOOD-GROWING

A SCAVENGER’S GUIDE

[RECYCLODYNAMIC GARDENING]

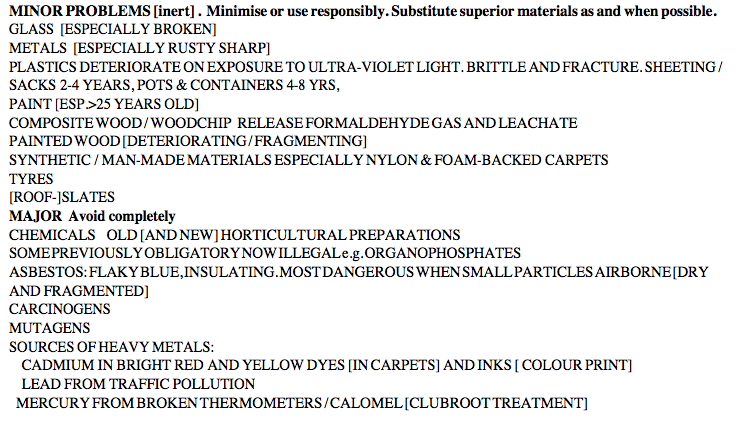

Recycling can often be limited in a domestic context by the space available. Gardening and allotmenting can provide many opportunites for extensive recycling and re-using a wide range of resources, from materials which will form permanent features [such as renovated buildings], through items which will be useful for several years [such as repaired tools], to matter which can be continuously collected and consumed [such as compostables]. This leaflet firstly attempts to list many different materials and their uses [1], according to how long they will last. Secondly it describes these same materials grouped according to what function [2] they perform in a growing system. It then suggests several likely sources [3] of freely available resources, grouped according to how far they need to be transported, and concludes with recommendations on what materials could be less helpful or even dangerous [4], especially in the context of growing organic food.

The most important criteria used for assessing all these resources is their suitability and safety for inclusion in food-growing systems. Compiled from ten years of experience of recycling for organic food growing in an urban context.

The defining characteristic of organic gardening and horticulture is an understanding of the many, diverse cycles involved in plant growth and the ability to harness them to improve the growing system. Remember that plants and gardens provide most of us with the only means of accessing and storing the abundant, renewable energy of the sun, the ultimate in sustainable power sources.

Consumables – [will last for a few years.]

SECOND-HAND / REPAIRED TOOLS / EQUIPMENT

SCAFFOLDING PLANKS

WOODEN GUTTERS

Permanent and semi-permanent – Materials which will endure indefinitely.

SUITABLE MATERIALS BY USE OR FUNCTION

If you remember everything that might have some use in your garden, you can easily source many of the materials you will need.

3. SOURCES OF MATERIALS.

ON-SITE CYCLES :

LOAM COMPOST LEAFMOULD LIQUID FEEDS MULCHES LIVESTOCK WILDLIFE

LOCALLY AVAILABLE :

[up to 1 km] DOMESTIC/ SKIPS / BUILDING SITES / INDUSTRIAL / SHOPS/ RETAIL / INSTITUTIONAL / MUNICIPAL MAINTENANCE

TRANSPORT TO SITE :

[5-10 km] LANDFILL INTERCEPT / DUMPIT SITES / COUNCIL SPECIAL COLLECTIONS/ SECONDHAND / EXISTING RECYCLING PROJECTS /

IMPORTS :

SEAWEED / ABATTOIR WASTES